April 2010

In This Edition

- Spring 2010 Docent Events

by Dennis Bires - Docent Spring Training

by Andrew Donovan-Shead - Massed Bison

by Dave Dolcater - Bison Tool Store

by Andrew Donovan-Shead - Where are the Monarch Butterflies?

by Van Vives - Dickcissel

by Nicholas Del Grosso - Visitor Counts

by Iris McPherson - How Ted Turner Scored Yellowstone’s Bison Herd

by Joshua Frank - Docent Coverage of Season Days

by Andrew Donovan-Shead - Tallgrass Prairie Preserve Visitor’s Center Latitude & Longitude

- Kiosk Maintenance

- Back Issues

- Newsletter Publication

Spring 2010 Docent Events

—Dennis Bires

- Saturday, April 24, 10:00 a.m. — 4:00 p.m.: Ranch Clean-Up Work Day. Please

meet at the Preserve Visitor’s Center, and bring a lunch. Participants will

clean up any debris left over the decades at the Florence Jones homestead

at the southern end of the Preserve. This is a small ranch that was purchased

by The Nature Conservancy a few years ago. What remains of the wooden ranch

buildings will be burned, and we want to clear the area of other evidence

of human habitation, including some fencing.

Please bring work gloves and rugged clothing and footwear, and any wire cutters, pliers, and claw hammers you may have. Please also pack a lunch and plenty of water.

Volunteers will assemble at two locations to begin the work day. Those who prefer to meet at the Visitor’s Center (where there are restrooms) should gather at 10:00 a.m. Anyone who would rather not drive to the Visitor’s Center then back to the south end may meet at 10:15 a.m. at the gate to the Jones property. To find it, drive north from Pawhuska on the county road, and less than 100 yards before reaching the cattle guard to enter the Preserve, stop at a pipe gate on the left, recognizable by the old tires around it. The two teams will meet at 10:15 or 10:20, and drive in to the work site.

Just after the lunch break, work day participants will take a short excursion to a neighboring tract that is leased by the Preserve to visit the John Joseph Matthews cabin. Matthews (1894-1979), a celebrated Osage author, refers to the cabin as the Sandstone House in his delightful 1945 memoir Talking to the Moon, republished by Oklahoma University Press and available for purchase in the Preserve Visitors Center. The house stands empty now, and Matthews’ final resting place is nearby.

- Saturday, May 15, 10:00 a.m. — 4:00 p.m.: Prairie Road Crew, Cookout,

and Hike. Docents and their guests are invited to join the Prairie

Road Crew, Cookout, and Hike.

Meet at the Visitor’s Center at the Preserve for roadside cleanup assignments at 10:00.

Plastic buckets, pokers, and trash bags will be provided.

Don’t pack a lunch, because at noon volunteers will enjoy the annual cookout at the Foreman’s House, near the Research Station. All victuals will be provided.

At 1:30, participants will drive to the site of a guided cross country hike on the Preserve, which will wrap up at about 4:00.

Feel free to attend any one or more of the three parts of this yearly social event. This is a good opportunity to introduce a friend to the activities of the Docent Program.

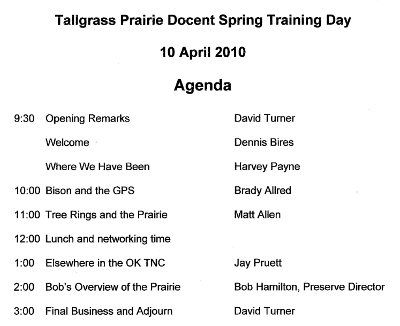

Docent Spring Training

—Andrew Donovan-Shead

David Turner convened the annual Docent Reorientation at 9:30 a.m. on Saturday, 10 April 2010, which he styled Docent Spring Training with the rationale that it isn't quite proper to be reorienting the attending new docents who have just been trained within the previous few weeks.

David recognized Harvey Payne’s service to the Preserve and to the Docent Program, asking him to reiterate the history of the preserve and how the Docent Program came to be, for the benefit of the new docents.

Harvey took the floor, expressing amazement at how many docents return year after year, driving hundreds of miles at their own expense. He said that the prairie magic is spriritually uplifting and that it must be this that makes docents return with such consistent regularity. A good thing too because the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve Docent Program has become the face of the Preserve; Harvey said that the office receives regular unsolicited calls from visitors expressing deep appreciation at finding knowledgable docents willing to welcome them and answer their questions about the Preserve and the mission of The Nature Conservancy.

Harvey said that the Docent Program grew out of the volunteers who joined together to make happen the inaugural release of 300-head of bison in 1993. The Preserve was created by the purchase of the Barnard Ranch in 1991, the result of a capital campaign begun in 1989, which was a big stretch for the Oklahoma Chapter of the Conservancy. The audacity of The Nature Conservancy paid off with the creation of a private preserve that rose from the ashes of a public misadventure.

Since the 1930s, the National Parks Service has wanted to create a tall grass prairie national preserve; unfortunately, the land has been too valuable to preserve because it is worth so much for food production and settlement. By the mid 1980s, a complicated public plan had been brokered with the help of Representative Mickey Edwards. All went well until another environmental entity insisted on the establishment of a wilderness area with no roads and with other restrictions; at the same time they initiated a lawsuit against the Parks Service in another part of the country. Representative Edwards withdrew his support and the plans for the Tallgrass Pairie Preserve collapsed in 1988.

From this unpromising beginning, the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve has grown to become self-sustaining on secure financial foundations. Bob Hamilton is the main architect of the preserve; he has facilitated a large quantity of science. Lessons from the Prairie, the First Twenty Years can be read via this link.

Harvey said that the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve Docent Program is one of The Nature Conservancy’s shining successes. He thanked the Docents again and relinquished the floor to David Turner.

David introduced Brady Allred, a graduate student of OSU, who presented a talk on Grazing Ecology at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve. Brady worked in conjunction with Sam Fuhlendorf, Dave Engle, Oklahoma State University, Bob Hamilton, and The Nature Conservancy.

Brady gave an excellent presentation of his work of which the key points seemed to be as follows:

- Historically, landscape is shaped by disturbance caused by climate, fire, and grazing.

- One species of herbivore is not inherently more destructive of range quality than another. Cattle have

been demonstrated to behave similarly to bison, as far as grazing and water use

is concerned.

- Received wisdom has been traced to a single questionable source.

- Fire is the strongest influence on bison, more so than water or topography. Fire drives bison grazing behavior, as it does the behavior of all herbivores.

- Fire influences grazing: grazing influences fire.

- Patch burning has been shown to be comparable to traditional range management

practices in terms of livestock growth. However, the benefits of patch burning

outweigh traditional management techniques by producing these outcomes:

- Dependable use of prescribed fires.

- Greater fuel loads for prescribed burning.

- Ability to use prescribed burning without defering grazing before burning.

- Does not require gathering or moving cattle before burning.

- Controls invasive species without chemical or mechanical methods.

- Creates heterogeneous landscape that provides economic, environmental, and ecological benefits.

- Provides rest for each portion of a pasture for 2 to 3 years.

- Achieves uniform distribution of grazing use over the entire pasture during a period of years.

- Manages for drought by stockpiling forage.

- Promotes less feeding of protein supplements in the winter.

- Provides habitat for species of wildlife native to grassland, shrublands, or forest lands.

- Fire stimulates the sequestration of carbon through improvements in the vigor of new plant growth. Photosynthesis is higher in areas recently burned. No one seems to know what the chemical balance-sheet is between what’s released through burning versus what is sequestered through improved plant growth.

In addition to Brady’s presentation material, I quoted from OSU Extension publication E-998 Patch Burning: Integrating Fire and Grazing to Promote Heterogeneity, section Why Implement Patch Burning on page 21, copies of which Brady made available as part of his talk.

After Brady Allred, Matt Allen gave a presentation prepared in conjunction with Dr. Michael Palmer entitled: Fire History of the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Osage County, Oklahoma. Brady derived his principle source of data from fire scars recorded in tree-rings revealed by sectioned trunks of fallen timber that were prepared in the laboratory. Matt’s research is an elegantly indirect method of reaching a firm conclusion about the fire history 277 years into the past, well into pre-settlement times when the prairie was the exclusive domain of the Native Americans. Key points of Matt’s work seems to be as listed here:

- There is no statistical relationship between fire and climate.

- There is evidence of fire in every time period assessed.

- Earliest fire appears during the year 1740.

- There is little change in fire seasonality over the period of record.

- Frequency of fire events has increased over the past 277 years, likely coincident with expansion of the cattle industry in the region.

- There is no significant climate effect, indicating an anthropogenic fire regime.

Matt concludes that the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve fire prescription appears fairly consistent with the pre-settlement fire regime. And, in contrast with much of North America, the fire regime on the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve appears mostly intact throughout its history; this is very good news because it means that, discounting the roads, oil wells and other structures, the Preserve landscape is a window into the distant past. The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve is proving to be a valuable laboratory.

We took a break for lunch outside at the picnic tables in balmy spring weather. Afterwards, we returned to hear Jay Pruett give a summary of the work conducted elsewhere in Oklahoma by The Nature Conservancy.

At the Keystone Ancient Forest Preserve, City of Sand Springs is wanting to sell the preserve to the State Parks in an effort to mitigate the city’s financial difficulties. The Nature Conservancy will continue ecological management of the preserve and there is a possibility that the Conservancy may get an opportunity to buy the preserve for a nominal sum of money. Keystone preserve needs a conservation area plan; there is a danger of wild fires caused by the high fuel load and the Conservancy is trying a find a way to prescribe a regular burn regime.

At Pontotoc Ridge, south of Ada, where the trees of the east meet the prairies of the west there is a need to burn. Work is needed to build good working relationships with the neighbors. Red cedar removal is proceeding well. Found in residence at the preserve is the critically endangered American Burying Beetle, Nicrophorus americanus, pictured at right.

Bowler Seeps & Sand Hills Preserve consists in 400 acres. Though small in size, it is interesting because it encompasses both wetland and dry sandy highland. Sadly, vandals destroyed the beaver dams with dynamite, draining the beaver ponds in order to net turtles for meat, principally the Western Prairie Chicken Turtle; so called because its meat tastes like chicken, a discovery made during the depression of the 1930s; The Nature Conservancy is helping the beaver to restore the dams and lodges. I thought I heard Jay say that the Conservancy is working with the Oklahoma Department of Transportation (ODOT) to add other areas.

Blue River is an aquatic preserve, the only undammed river in Oklahoma. It is a new acquisition consisting in 9,000 acres. It has invasive species of Yellow Iris and Koi fish.

Four Canyon Preserve is five years old. New species of trees have been discovered through hybridization of oaks. It is free of red cedar trees. Cattle have been returned to the land in conjunction with patch burning.

Black Mesa preserve is isolated in the Northwestern corner of the state. The Nature Conservancy provides conservation management and works to install conservation easements in the surrounding area.

Cucumber Creek preserve has invasive species and lacks a fire regime.

The Tallgrass Prairie Preserve has an abundance of American Burying Beetles. This means that the preserve receives funding related to nationwide beetle conservation efforts. These funds are being used to expand the Preserve through the purchase of in-holdings.

At the Nickle Preserve the elk herd has grown to approximately 50-head and an elk hunting season has been restored in the surrounding area. The preserve was completed by the purchase of an in-holding that is being restored by returning it to open forest, helping to dry out the ground thus reducing the population of snails and brainworm parasites that can infest the elk. The preserve has invasive Teazle and Nepalese Browntop. Recently, thieves stole the management equipment from a barn. An insect research program is being conducted to measure overall ecological health.

The Nature Conservancy has three preserves underground. A captive breeding program has been established to guard against the depredations of White Nose Syndrome among the bat populations. The syndrome has the effect of waking the bats more frequently during hibernation, causing them to burn more energy reserves and thus starve to death.

Springer Prairie still belongs to the Conservancy. It consists in 40 acres of land.

Bob Hamilton said that the struggle against Serecea Lespediza continues. Last year 2,600 man hours were spent spraying the plant. The Preserve has been awarded a USDA grant to study improved methods of controlling Serecea through a combination of patch burning and grazing overlayed by spot spraying. Fire removes the woody growth which makes the new growth unpalatable to grazing animals. Later on, the plant accumulates tannins that make it objectionable.

A stream restoration project is returning the streams closer to their ancient profiles. The bunkhouse is being restored to improve moisture control through the addition of ceiling fans. A paper has just been published that summarizes the first twenty years of work at the prairie. A copy is available on-line in the docent library.

David Turner closed the meeting at about 3:15 p.m.

Massed Bison

—Dave Dolcater

Saturday, March 6, 2010: After helping with the Prairie Road Crew earlier in the day, I decided to drive the bison loop on the way back to Tulsa. The landscape on the south side of the loop from the western preserve boundary all the way to Hickory Creek was filled with bison — possibly 3/4 of the entire herd, maybe 1,500 animals. As I drove east, every hilltop revealed yet another magnificent view with bison in all directions. In my 15 years volunteering at the prairie I’ve never seen that many bison on the open range.

Driving on toward Pawhuska I met an obvious tour group, a caravan of two minibuses and one pickup truck, just west of the monument at the south entrance to the preserve. They were planning to see some bison then spend the night in Arkansas City. My watch read 5:30 — only 52 minutes until sunset! I lead the group through the bison with stops for pictures. Very few people visiting the prairie get to see that many bison, and we drove right through the middle of them. The sun had set by the time we reached Blackland and we drove on to the Foraker road so they could go straight west to Highway 18 then on to Kansas.

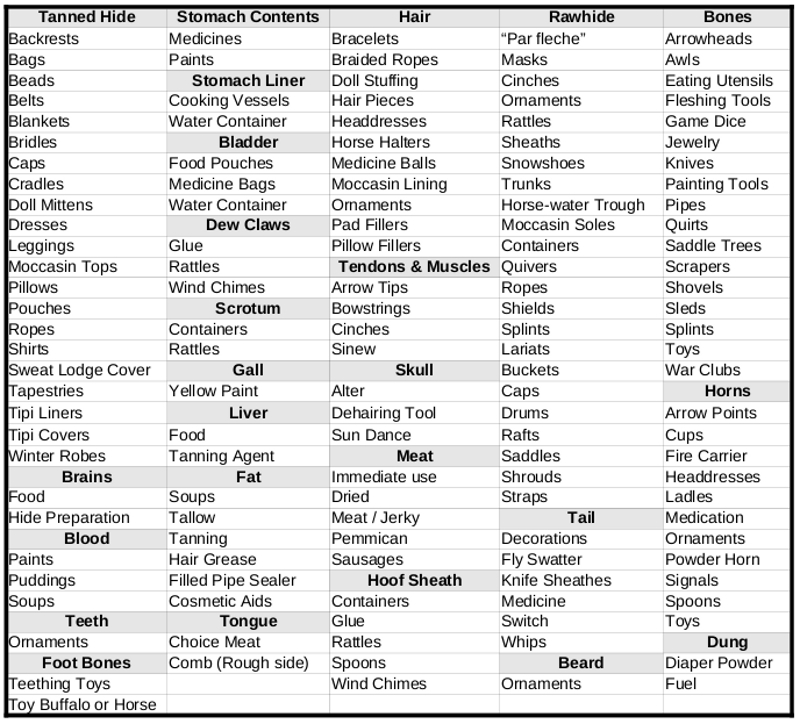

Bison Tool Store

—Andrew Donovan-Shead

Earlier this year, while on my way to Florida, I stopped at the Adai Indian Nation Cultural Center, just outside Natchitoches, LA. During my visit, I noticed a display describing the Traditional Uses of the Buffalo. To paraphrase the sales slogan of a forgettable beer: Native Americans reach the parts other cultures miss.

Where are the Monarch Butterflies?

—Van Vives

Have you noticed that you are not seeing as many Monarch Butterflies this year? Don’t blame it on poor eyesight. Yes, they are dwindling rapidly in number. In the 1980s there were 170,000 of the species that wintered upon the Natural Bridges State Beach in Santa Cruz, CA. This year there are only 3,800.

There are two groups of Monarchs naturally divided by the Rocky Mountains. The eastern group travels from Canada to Mexico, a 3000 mile journey. Scientists believe there are several reasons for the downward spiral.

The continued deforestation in areas where the Monarch usually winters is one reason for the decrease, especially in Mexico. A second reason is the loss of habitat in the United States. Any species that depends on one food source is especially vulnerable. The Monarch feeds exclusively on milkweed and deposits eggs exclusively on the milkweed plant. When lands are converted for special uses, herbicides are used to kill the unwanted milkweed.

Another reason for the loss is climate change. The butterflies can not survive a climate that is warming up, and they can not stand cold extremes. The changes in rainfall and warming temperatures tend to dry up water sources which they need.

Another surprising aspect is that the number of female Monarchs has been dropping. Perhaps that is Nature’s way of adjusting populations to availability of food, land, and water. Research at the University of Georgia has shown that in the 1970s 54-percent of all Monarchs were female. Today there are only 43-percent females.

A group called Monarch Watch has been promoting the cultivation of milkweed by businesses, parks, conservation groups, individuals, and governmental agencies.

We will have to wait and see what success they have.

Dickcissel

—Nicholas Del Grosso

The Dickcissel arrives on the Great Plains breeding grounds towards the end of April. The male, at six inches, looks like a pigmy Meadowlark, with brownish upper colors with a yellow breast and a black bib. Females look like House Sparrows. These birds are not very musical; their call is made up of three dry, rasping parts sounding like dick dick dickcissel. They also make a short buzzy call as they fly. This call is actually used to maintain contact with the group during their night migrations.

Dickcissel’s like moderately tall dense prairie vegetation. When you are hiking the three mile trail look for them calling from the tops of big bluestem or shrubs, typically you will see several males trying to out-sing each other. When you see this little ball of brown and yellow or hear their call, which sounds like an upset locust, remember they began their journey at night from the Llanos of Venezuela. They probably flew up through Central America into Mexico and across the Rio Grande River into Texas. There are even sightings of Dickcissel’s flying across the Gulf of Mexico resting along the Gulf Coast and dispersing across the Midwest. This one-way migration takes the Dickcissel over 7000 miles.

The breeding season lasts from May through July. The female weaves a nest from course grass lined with smaller grasses and rootlets. You will usually find the nest in forbs, shrubs, grasses or trees about 10 inches from the ground. The female will lay 3-5 eggs which are incubated for 12 days. The female cares for the young which leave the nest in 9-10 days. The diet of breeding adults is 70-percent insects and 30-percent seeds. Outside the breeding season, Dickcissel’s feed mostly on seeds, including weed seeds and cultivated grains.

Studies by the Oklahoma Breeding Bird Atlas have verified that Cowbirds regularly parasitize this species. In Oklahoma the Dickcissal population has increased 1.1-percent per year, but range wide it has registered a decline of 1.4-percent per year. The major threat to this species comes from its wintering grounds in Venezuela. Because of the tendency of this species to gather in large flocks, often numbering over a million birds, it can take a toll on a farmer’s rice or sorghum. It is a serious agricultural pest in Venezuela and farmers have sometimes taken to trying to poison flocks. In an attempt to alleviate the problem Venezuela Audubon has established an agreement with Venezuelan Farmers Associations to develop a management plan for the species.

The conservation status of this bird is one of least concern. Here at the Tallgrass Prairie we can look forward to seeing this bird and enjoying its song and displays in the old growth grasses during its spring sojourn.

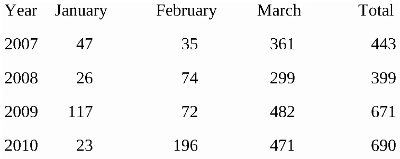

Visitor Counts

—Iris McPherson

I am combining the first 3 months of visitor counts for 2010. There were 23 people from 5 states who signed in during January, and 196 people from 10 states who signed in during February. The February count was really boosted with 150 Young Farmers and Ranchers signing in. I’m not sure if that group was an Oklahoma group or whether there were people from other states included, so I just added them all to the Oklahoma count. We had a good representation of visitors in March with a total of 471 from 28 states and 8 countries. One ironic thing showed up though, after Wyoming being the only state last year that was not represented, we had a group of 5 people from that state in March. There were 296 from Oklahoma with Kansas (23), California (18) and Texas (13) with the next highest numbers. The highest number of international visitors came from England with 16.

The history of count for the first 3 months for the past four years is shown right.

As you can see, we are off to a good start this year. I think a part of the increase in number of visitors is due to the docents’ effort to get the people who come to the gift shop to sign the register, so we can get a more realistic count. Thanks for all of your efforts on this, and keep up the good work.

Please remind the visitors to sign the guest register.

How Ted Turner Scored Yellowstone’s Bison Herd

—Joshua Frank

Yellowstone buffalo, despite being on the verge of extinction, have virtually

no protections in the West. And media mogul Ted Turner’s going to cash in on it....

Read the article by following this link: http://www.truthout.org/how-ted-turner-scored-yellowstones-bison-herd58341.

Read what the Bison said by following this link: Bison Bison.

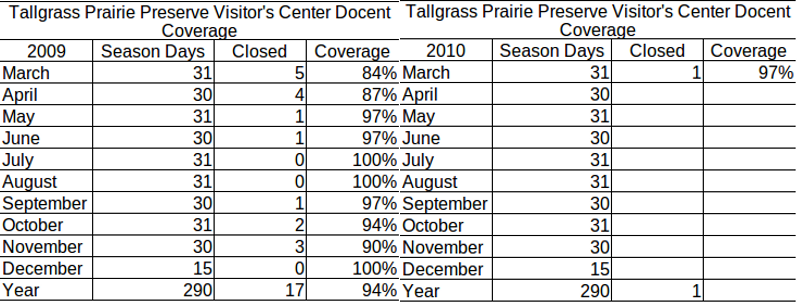

Docent Coverage of Season Days

—Andrew Donovan-Shead

We have got off to a good start with only one day closed in March.

Tallgrass Prairie Preserve Visitor’s Center Latitude & Longitude

Here is the latitude and longitude of the Visitor’s Center that you can give to visitors for entry into their GPS navigation device.

- N36° 50.774′

- W096° 25.381′

Kiosk Maintenance

The manufacturer’s instructions for cleaning the touch-screen recommend use of a soft dry cloth only. This proved inadequate for smeared fingerprints. Soft-paper kitchen towels work well, slightly damp with a small drop of soft handsoap. Application of a dry kichen towel removes any residual moisture.

Over time, a matter of several weeks continuous operation, I have noticed that the calibration of the touch-screen drifts away from the initial set-point. If you notice that the cursor isn’t under your finger when you touch the screen then restart the kiosk by unplugging it from the wall, waiting a few moments and then re-inserting the power plug. It will restart and recalibrate.

This link points to the complete Kiosk Maintenance Manual.

Back Issues

Back issues of the Docent Newsletter, to February 2009, can be found in the two green and one blue-black zip-binders, stored in the Perspex rack by the file cabinet in the office of the Visitor’s Center.

Newsletter Publication

Deadline for submission of articles for inclusion in the newsletter is the 10th of each month. Publication date is on the 15th. All docents, Nature Conservancy staff, university scientists, philosophers, and historians are welcome to submit articles and pictures about the various preserves in Oklahoma, but of course the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in particular.